GE distributes dollars to influence river debate

May 4, 2011

By David Scribner

Illustrations by Honora Toole

PITTSFIELD, Mass.

On a spring morning, the 262-acre Audubon Society wildlife refuge known as Canoe Meadows is bustling with activity.

Redwing blackbirds cling to tawny cattail stalks, clucking a warning as hikers stride by. Pairs of ducks swim companionably in the broad, dark arc of the Housatonic River that coils through the conservation area. Even the spring peepers, not yet exhausted from a night of screeching debauchery, are still calling to each other.

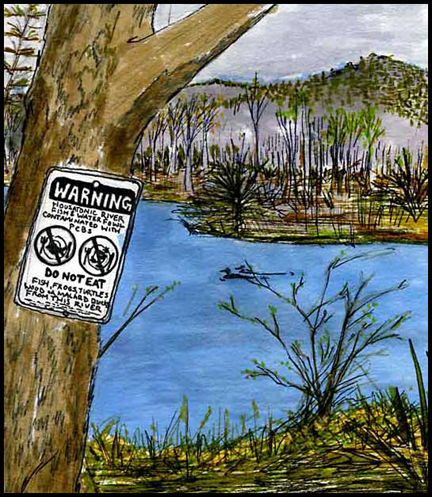

Canoe Meadows, in the southeastern corner of Pittsfield, is as richly diverse a river and floodplain ecosystem as there is in the Berkshires. But appearances can be deceptive. For the Housatonic is a poisoned river, polluted by the former General Electric plant a couple miles upstream, where for 45 years the company allowed 1.5 million pounds of PCBs, a probable carcinogen and known growth and hormone disruptor, to seep into the river and collect along its banks and floodplain.

“It would appear to the naked eye that nothing is wrong with the Housatonic,” explained John Lortie, a wildlife biologist who has studied the river for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “That is not the case.”

But the seemingly idyllic environment at Canoe Meadows could become the setting for a kind of demonstration project that might set the stage for a restoration of the entire Housatonic River, which flows south from Pittsfield into Lenox and Great Barrington, then on to Connecticut and Long Island Sound.

George Wislocki, a former director of the Berkshire Natural Resources Council and longtime environmental advocate, has proposed that the EPA use Canoe Meadows, this small section of river, as a test site to demonstrate that its methods of extracting PCBs from a badly contaminated environment – even if it involves dredging and trucking the polluted river sediment away — can indeed result in a river that recovers its former healthy, flourishing condition.

Wislocki argues that if the EPA could succeed at Canoe Meadows, it could succeed in removing PCB sediment elsewhere along the winding, rural course of the Housatonic.

And that, he says, would foil General Electric’s claims that intensive removal of PCBs would be too messy, disruptive and destructive to the environment.

“Show the people of the Berkshires what restoration will look like,” Wislocki said. “As it stands today, many people are none too sure that the EPA and GE have the ability to restore the river so that it remains a jubilant place for wildlife and for people.”

Wrecking a river to save it?

The debate over how and whether to clean up PCB pollution in the Housatonic has been roiling the Berkshires in recent months, with most environmentalists pushing for a ambitious effort to remove the chemicals while GE argues for a minimalist approach. The EPA is expected to settle on a cleanup strategy later this year, and GE, as the company that caused the pollution, is expected to be responsible for the cost of that work.

What particularly upsets Wislocki and other environmentalists is GE’s claim – echoed by allies the company has cultivated among the local business and cultural elite – that the act of cleaning up the company’s toxic wastes would be too ecologically destructive to be worthwhile.

Since January, GE’s claim that ambitious cleanup would be counterproductive has been picked up and repeated by an unusually broad range of local business leaders and institutions, from the director of the Norman Rockwell Museum to officials at The Colonial Theatre and the parent company of The Berkshire Eagle, the local daily paper.

Critics say the campaign against a full-scale cleanup is the result of an aggressive, behind-the-scenes organizing effort by GE and its allies – an effort they say has included cash grants from the company and the threat of withholding donations to nonprofit groups that fail to support the company’s position. GE and its supporters deny using any pressure tactics.

Echoes of Hudson debate

The claim that cleaning up PCBs would actually be bad for the environment may seem eerily familiar to people along New York’s upper Hudson River, where GE released an estimated 1.9 million pounds of PCBs from its Hudson Falls and Fort Edward plants from the 1940s until PCBs were banned in 1977.

In 1984, the EPA designated a 40-mile stretch of the Hudson a Superfund site, putting GE on the hook for hundreds of millions of dollars in potential cleanup costs. By the late 1990s, as the EPA weighed the scope of cleanup work it might require, GE was mounting a massive public relations campaign against the idea of full-scale dredging of the Hudson.

In television and newspaper ads, billboards, lawn signs and direct mailings to area residents, GE urged the public to “stop the dredging.” TV ads contrasted idyllic scenes of the Hudson Valley with images of the huge, muck-laden clamshell excavators that, the company warned, a massive cleanup would unleash. One newspaper ad declared dredging would “disrupt life on the river for years, and there’s no guarantee it will work.”

By the time it stopped accepting public comments a decade ago on how to clean up the Hudson River Superfund site, the EPA had received 73,000 individual comments. But despite GE’s public relations campaign, the EPA issued a Record of Decision in February 2002 directing the company to dredge and remove 2.65 million cubic yards of PCB-contaminated sediment from the Hudson.

The cleanup was supposed to begin in 2005, but because of protracted negotiations with GE, the work didn’t actually get started until 2009. By the end of that year, GE completed Phase I of the Hudson cleanup, removing an estimated 293,000 cubic yards of polluted sediment from five miles of the river, at a cost of $560.9 million. This month, GE will begin Phase II, a much more extensive project covering 35 miles.

Although GE appears to have accepted the EPA’s stance on the Hudson River cleanup, it still has at least one legal challenge pending. A federal court dismissed the company’s challenge to the Superfund law, but the company has appealed that ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court has yet to decide whether to hear the case.

Stirring up opposition

In contrast to the Hudson River site, GE avoided a Superfund designation for the Housatonic in 1999 by signing a consent decree under which it agreed to clean up a 2-mile stretch of the river in Pittsfield and then negotiate with the EPA on what to do about the river south of that stretch. The first phase alone cost the company hundreds of millions of dollars.

Now GE faces the far costlier phase, following the serpentine course of the Housatonic to the south, where PCBs have spread into surrounding agricultural and residential floodplains and collected in the ponds behind old mill dams.

Just as it did for the Hudson 10 years earlier, the EPA has begun the process of determining what level of cleanup GE should undertake to remove PCBs from “the rest of the river.” The agency is expected to issue its findings this fall.

As a first step, GE submitted a study late last year detailing its recommended approach to PCB cleanup. That approach, which the company calls “monitored natural recovery,” essentially would let the PCB concentrations break down naturally rather than disrupt the river environment with invasive dredging or other removal techniques. But because PCBs don’t break down easily in the environment, EPA consultant Richard McGrath has estimated this “natural recovery” wouldn’t be completed for centuries, “if at all.”

Meanwhile, just as it did along the Hudson a decade ago, GE is mounting an increasingly vigorous publicity campaign aimed at discrediting the EPA’s conclusions and influencing elected officials, EPA administrators and public opinion.

As alternative to monitored natural recovery, the company offered a proposal to remove PCBs from the river and dump the contaminated sludge in three capped landfills it would create in Lenox, Lee and Housatonic. This idea immediately provoked opposition from town officials and residents.

Dire predictions of local toxic waste dumps were also prevalent in the early years of GE’s campaign against cleaning up the Hudson. The issue wasn’t put to rest until the EPA pledged unequivocally that any PCB-contaminated wastes from the river would be taken outside the region for disposal.

“The tactics GE is using in the Berkshires resonate with us,” said Rebecca Troutman, a staff lawyer at Hudson Riverkeeper Inc., which spent years pushing for the Hudson PCB cleanup. “They seem exactly the same. But the fact is GE has to be held accountable for the pollution it caused. And we’ve seen that dredging works. PCB levels in fish, for example, have declined much faster than was expected, down to acceptable, normal levels.”

Front group for a polluter?

GE’s tactics along the Housatonic have been updated and refined. Its public relations campaign is unfolding online rather than in print, on social networking sites that nurture the Berkshires’ boundless capacity and appetite for intrigue.

Early in January, during the period in which the EPA was still accepting public comments about what approach to take with the Housatonic cleanup, a new Facebook page appeared on the Web. The page for the Smart Clean-up Coalition was recommended in online “likes” by the leadership of the Norman Rockwell Museum and by the Berkshire Creative Economy Council.

The Smart Clean-up Coalition did not initially identify its backers, or its origins, but it urged Berkshire residents, including those linked to cultural organizations allied with the Berkshire Creative Economy Council, to write the EPA and argue against any dredging of PCB sediments as too environmentally disruptive.

“We’re against any dredging at all, even in Woods Pond in Lenox,” said Norman Rockwell Museum Director Laurie Norton Moffatt, a Berkshire Creative co-founder, who used her Facebook friends list to endorse the Smart Clean-up Coalition. In her message she included a photo of the Housatonic River near the Rockwell Museum and warned that an EPA order for dredging would destroy the river environs near the museum, despite the fact that the EPA had never considered PCB removal along the river in Stockbridge.

“Extensive dredging would devastate the river and negatively impact tourism, the Berkshire County economy and our quality of life for years, if not forever,” she wrote.

Soon, however, one of Smart Clean-up’s sponsors came to light. In response to a query from Housatonic River Initiative founder Tim Gray, the coalition at first denied that it had any association with General Electric, even though its advocacy was similar in tone, language and images to the messages on GE’s own Housatonic River Web page.

It turned out that the Smart Clean-up Coalition was an initiative of 1Berkshire, an alliance of three Berkshire business development groups: the Berkshire Visitors Bureau, Berkshire Chamber of Commerce, and the Berkshire Creative Economy Council.

In January, a $300,000 contribution from General Electric appeared on the books of 1Berkshire, whose purported mission is to foster economic development in the county. Immediately, development of the Smart Clean-up Coalition social network Web page began under the guidance of Berkshire Bank, whose chief executive, Michael Daly, also serves as chairman of 1Berkshire.

“Smart Clean-up Coalition is not working with GE in any way, shape or form,” Daly insisted at the time, though he conceded 1Berkshire had received GE backing and that, in fact, GE was a founding partner.

He did not mention another GE connection to the bank. Berkshire Bank’s “non executive chairman” is Larry Bossidy, a Pittsfield native who was a top executive at GE for 34 years and a close confidante of Jack Welch, GE’s longtime chief executive.

Resigning in protest

Environmentalists say former state Rep. Peter Larkin of Pittsfield and former Massachusetts Secretary of Environmental Affairs Bob Durand, both now lobbyists for GE, were influential in securing the company’s donation to 1Berkshire at a meeting in the fall with Daly and other 1Berkshire allies.

Daly’s disavowal of GE influence was not convincing to some 1Berkshire members, especially those affiliated with Berkshire Creative, an association linking cultural organizations and artists with entrepreneurial opportunities.

Two 1Berkshire directors — Eugenie Sills, founder of The Women’s Times, and filmmaker John Whalan — resigned in protest. They objected to what they described as the covert way in which the decision to take GE’s side on the cleanup was made. They also decried what they said were 11th hour strong-arm tactics applied to 1Berkshire directors to get them to go along with that decision.

Whalan said he was particularly incensed at the tactics of nonprofit Berkshire Bank Foundation, upon which many local cultural organizations rely, in part, for their support. The foundation’s executive director, Peter Lafayette, sent repeated e-mails to his nonprofit applicants and grant recipients urging them to write the EPA endorsing a minimal PCB cleanup.

“It’s unconscionable and unethical,” Whalan said, noting that nonprofit agencies might well feel obligated to write such letters so as not to jeopardize a foundation grants upon which they depend, especially given that the recession has slowed donations from other sources.

Daly, however, denied that the bank’s e-mail entreaties were meant to pressure nonprofits into supporting Smart Cleanup.

“Participation in the Smart Cleanup does not affect or influence funding allocations, and no such e-mail was at all intended to indicate otherwise,” he said.

The two co-chairs of the Berkshire Creative Economy Council — Nancy Fitzpatrick, owner of the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, and Studio Two photographer Kevin Sprague of Lenox – also disputed the claims of impropriety.

“The circumstances by which Berkshire Creative finds itself included in the river issue is primarily a function of our involvement in 1Berkshire,” Fitzpatrick and Sprague said in a joint statement. “The Smart Clean-up coalition was an outgrowth of an initiative that came up late last year, when members of the board of 1Berkshire proposed that the organization should be involved in the river dialogue. GE has been on record as one of a number of prominent regional corporate sponsors of 1Berkshire. The timing of their contribution and the solicitation happened independently from the creation of the river initiative and the letter-writing campaign.”

Benefits of a cleanup

Amid this perfect storm of conflicting agendas, seen and unseen, the EPA has attempted to forge ahead with its assessment of feasible cleanup strategies.

In the first week of April, the agency conducted three public mini-workshops at Shakespeare & Company’s Founder’s Theatre in Lenox. At these sessions, a panel of EPA engineers, botanists, ecologists and chemists presented their analyses of the river’s history, the risks of PCB contamination and potential cleanup strategies.

To an audience that included delegates from 1Berkshire as well as environmentalists and representatives of GE, the agency’s experts insisted that removing PCBs would result in a healthier ecosystem, based on experiences at other contaminated sites. The entire session was recorded by cameramen for GE, which offered Web viewers live commentary on the proceedings by its own panel of experts.

Lortie, a biologist the EPA hired as a consultant, said the vitality of an ecosystem actually increases dramatically after PCBs have been removed, even when dredging has been applied.

“We have found diversity and abundance of species has increased,” he said. “Resilience is extraordinary.”

And the Housatonic ecosystem needs restoration, he added.

“Every species we sampled, from insects to algae, to mammal to waterfowl, had high levels of PCBs,” Lortie said. “There is absolute proof of tissue accumulation of PCBs.”

As a result, he said, bald eagles living along the Housatonic are no longer able to breed successfully, and the populations of mink and otter, both particularly vulnerable to PCB toxicity, were smaller than in comparable, uncontaminated environments.

Biohabitat consultant Keith Bowers argued that removal of PCB-polluted sediments combined with a restoration plan would “drastically reduce and accelerate the recovery time of the river habitat,” ultimately resulting in a river environment more diverse and vibrant with wildlife and plant species.

Susan Svirsky, the EPA’s Rest of the River project manager, said the agency would be guided by a “surgical mindset” in determining the extent of the cleanup operation. She added that though the cleanup would likely take a number of years and be “painful,” the river and its environs would quickly heal.

“PCBs pose a real risk to human health and to the health of many species that lives along the Housatonic, and these risks will last at least 250 years unless the contaminants are removed,” Svirsky said. “Our goal is to have a restoration that results in a permanent reduction in health and environmental risks. This will become a floodplain that will regain its natural beauty and habitat quality, with no long-term loss of species.”

1 comment for “GE Distributes Dollars to Influence River Debate”