By David Scribner

October 23, 2011

LENOX – Even as the state Department of Environmental Protection presses ahead with its campaign for a minimal cleanup of (PCBs) from the Housatonic River floodplain, the federal Environmental Protection Agency, which will have the final say on the cleanup approach and scope, is denying claims that it is under pressure from the White House to adopt the state’s less invasive criteria.

“This is simply not true,” declared EPA Region 1 Administrator Curt Spalding. He said that the agency was not under political pressure to “choose a Housatonic River cleanup plan that won’t protect the health of people or the environment in Berkshire County.”

In a prepared statement, he continued: “I have stated repeatedly that the EPA’s guiding principal as we identify a cleanup plan for the Housatonic is that we will rely on the best scientific evidence to determine what measures need to be taken to ensure that we are protecting peoples’ health and restoring the Housatonic to good ecological health. I remain committed to an open, inclusive and transparent process that is allowing the communities of the Berkshires to weigh in with their concerns and priorities for the Housatonic River.”

“The assertion published in the Berkshire Record last week mistakenly states that the EPA is under political pressure to not pursue a health-protective cleanup plan for the ‘Rest of the River’ portion of the Housatonic,” wrote David Deegan, a spokesman for the EPA’s Region 1 office in Boston.

On October 9 in Great Barrington, Housatonic River Initiative Executive Director and co-founder Tim Gray had informed a gathering of 100 Occupy Wall Street sympathizers that sources within the EPA had told him that the White House had intervened in the debate on behalf of a less comprehensive cleanup strategy.

“It’s time for a reality check. Everyone here was scratching their heads, wondering where this idea came from, because we haven’t heard from the White House,” Deegan said in an interview from his Boston office. “It isn’t accurate. It’s just not true.”

After months of public input and decades of scientific research, the EPA is drafting a proposed remedy for removing PCBs, deemed a probable carcinogen and developmental disruptor for humans and wildlife that was spilled into the river over a 40-year span from General Electric’s manufacturing facility in Pittsfield. The EPA expects the document to be ready for public review early next year.

The release of the EPA’s cleanup recommendation has been delayed so that the EPA regulators could meet with their counterparts at the state DEP to discuss their disagreement over the competing river cleanup plan.

According to EPA spokesperson Jim Murphy, two sessions with DEP personnel are scheduled for October, and six more in November.

“There are a lot of stakeholders in this process, and part of our job is to evaluate public comments, in light of what the science tell us,” Murphy said.

Still, the painstaking process by which the EPA is developing its remedy has been challenged by powerful political forces.

This summer, when an early draft of the EPA report was submitted to a national EPA peer review board both U.S. Sen. Scott Brown and John Kerry, joined – surprisingly – by Congressman John Olver (D-Amherst), urged a postponement of the review, describing the EPA draft as a rush to judgment. Their letters supported a similar recommendation from DEP Commissioner Kenneth L. Kimmell.

Despite this unusual attempt to intervene in internal EPA deliberations, the review board did convene and consider the Housatonic River cleanup proposal.

But this has not stopped the DEP and its corporate allies, including 1Berkshire, the General Electric-funded alliance of local business organizations, from developing and promoting its own cleanup strategy in an apparent attempt to head off what is likely to be a far more rigorous cleanup program from the EPA. Helping to persuade local sportsmen and environmental groups to support a minimal cleanup is former DEP Commissioner Bob Durand, now a lobbyist for General Electric.

Massachusetts Departments of Environmental Protection and Fish and Game address crowd at Lenox Town Hall. Commissioner Kenneth Kimmell is fourth from left. - Photo: David Scribner

At a hearing last week at Lenox Town Hall, current DEP Commissioner Kimmell outlined the DEP’s strategy. It might be called the 25 percent solution, and Kimmell pointed out that it had been approved by the governor’s office.

To reach the meeting room, DEP officials had to make their way through a crowd of 100 demonstrators protesting both the DEP’s reported watering down of its cleanup recommendation and what they perceived as the influence of General Electric on their methodology and conclusions.

Demonstrators call for a comprehensive PCB cleanup of the Housatonic River in front of Lenox Town Hall - Photo: David Scribner

What the EPA will propose has yet to be disclosed.

“In the Housatonic floodplain we have one of the most fragile and pristine areas in the Commonwealth,” Kimmell told the crowded meeting room.

He argued, based upon the advice of biologists from the Department of Fish and Wildlife, that only 25 percent of the PCB contamination should be removed.

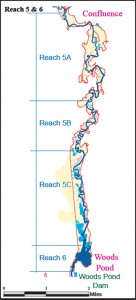

“We propose a massive removal of PCBs from Woods Pond, where 25 percent of the PCBs reside,” he explained. But he insisted that removal of the toxic industrial compound from the floodplain would be too destructive to the environment, and the DEP is suggesting remediation be undertaken in only 33 acres of the floodplain.

“We would excavate where necessary, but leave the rest of the PCBs in place,” he said. The DEP is advising that the PCB-laden sludge from Woods Pond should be shipped by out of state to a licensed toxic landfill.

Dennis Regan, Housatonic Valley Association Berkshire Director calls for thorough cleanup. - Photo: David Scribner

He also proposed a program of “adaptive management” that would employ emerging technologies to remediate the floodplain as they became available.

Fish and Wildlife Commissioner Mary Griffin agreed with Kimmell’s assessment. “We are faced with a suite of unpleasant choices,” she said before a standing-room-only crowd. “There is no magic bullet. This is an ecologically unique area, and the subject of a comprehensive ecological field study.”

Griffin and Kimmell asserted that “despite the contamination” there was a robust population of species in the watershed.

They maintained that there was “no adverse effects” to the wildlife populations, nor PCB contamination in sufficient concentrations in the flood plain to pose a human health threat. They further insisted that it is critical to retain the “meandering” course of the river essential to sustaining biodiversity, a twisting river channel they claim would be jeopardized by the thorough removal of PCBs from the riverbanks and floodplain.