By Mickey Friedman

August 12, 2011

GE sees Rising Pond and sees a PCB dump. I see Rising Pond and I see a gem, the cornerstone of a renewed and restored Housatonic, Massachusetts.

I see people fishing on the banks, and community picnics. I see families swimming. Summer nights and fireworks.

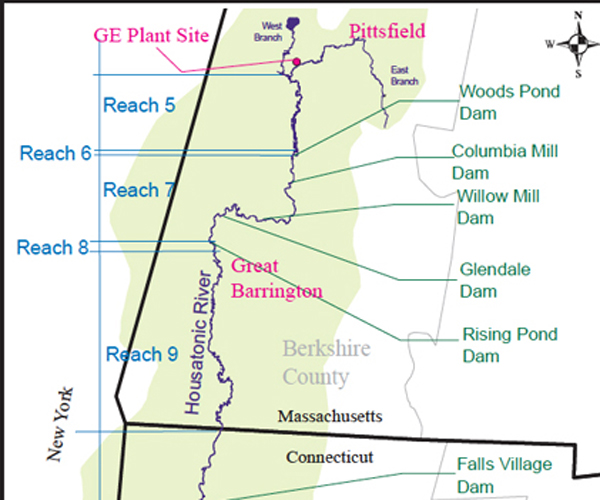

GE’s 2010 Corrective Measures Study (CMS) offers a range of cleanup alternatives for the Rest of the Housatonic River. The 1200 page CMS is not easy to navigate. They’ve divided the river into various reaches: 5a, 5b, 5c from the confluence of the East and West Branches to Woods Pond, then Reach 6 for Woods Ponds, Reach 7 down to Rising Pond, which is Reach 8, while Reach 9 goes to the Connecticut border.

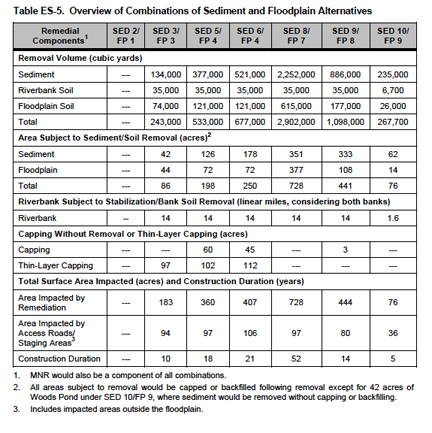

Then they’ve come up with a bunch of options for cleaning up sediments (their SEDs) and different options for cleaning up floodplain soils (their FPs.) Then they mix and match. The chart below shows some of the combinations GE has come up with. It gives you an idea of how much river sediment and river bank soil they might remove in each scenario, how big an area that involves, how much capping or covering up that might entail, and how long they estimate it might take.

Many of the plans leave Rising Pond the way it is, contaminated with GE’s polychlorinated biphenyls. Granted, Rising Pond has lower levels of PCBs than other portions of the river, but it is contaminated and you shouldn’t eat the fish or ducks or frogs and you shouldn’t swim it.

Two of GE’s favorite scenarios – its No Action and Monitored Natural Recovery plans – require no cleanup activities at all for the entirety of the Rest of the River. Others would require GE to do, begrudgingly, of course, at least some remediation. In those cases, GE will have to dispose of the contaminated bank soil and river sediment it takes from the river.

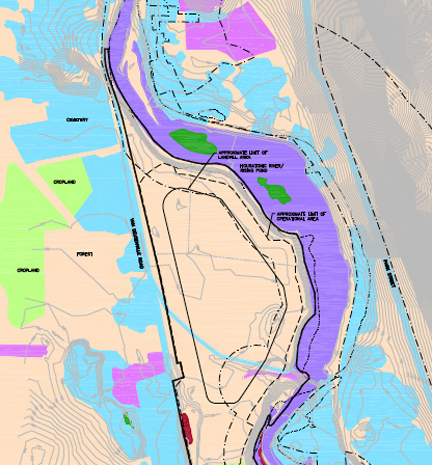

That’s where GE thinks Rising Pond will prove useful: an Upland Disposal Facility. A PCB dump.

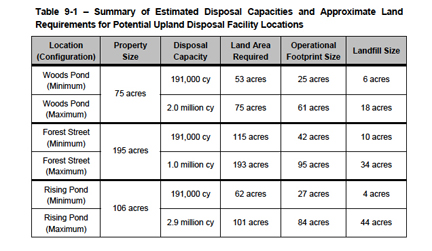

GE purchased three lots totaling 106 acres by Rising Pond, outside the 500-year floodplain. Depending on which cleanup scenario EPA orders and how much contaminated soil and sediment GE has to dispose of, they would like to use anywhere from 62 to 101 acres of that land for their landfill. According to the calculations below, the Rising Upland Disposal Facility would have the largest capacity of all of the landfills they’ve proposed:

I have a better idea for Rising Pond and the land bordering it. Turn my dream into reality. Completely clean and restore Rising Pond.

Unfortunately, it’s an unlikely dream. Most attention is focused on the ten miles from the confluence of the East and West branches to Woods Pond. And unless the people of Great Barrington loudly, and in large numbers, insist on a cleanup of Rising Pond, the Rest of the River cleanup will most likely end at Woods Pond.

These are easy battles to lose. GE won the right to massively expand its Hill 78/ Building 71 landfill, even though their PCB dump sits across the road from Pittsfield’s Allendale elementary school. And Pittsfield just recently lost its chance to clean its own little jewel of a waterway right in the midst of the city. A fishable, swimmable Silver Lake could have re-energized efforts to revitalize the old GE facility. But because the people of Pittsfield stayed silent, and local leaders were compliant, Silver Lake will not be dredged, its PCB and other toxic contamination covered and capped by a layer of sand. No one will be swimming in Silver Lake.

Why clean Rising Pond? According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), the PCB levels in Rising’s fish are “still significantly elevated. The highest levels were found in Brown Trout, Largemouth Bass, and Brown Bullhead (catfish).” A brown trout had PCBs levels of 33 parts per million (ppm); Largemouth Bass had average PCB levels of 14.3 ppm. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests a tolerance level of 2 ppm in fish you eat, but some river advocates think a safer level is 0.5 ppm. That Brown Trout’s got 16 times the safe level of PCBs. Don’t eat it.

Because there are low levels of PCBs in the soil around Rising Pond, it’s unlikely the EPA would consider cleaning them.

But there’s a case to be made for removal of the PCBs from Rising’s sediments. There’s an average concentration of 4.2 ppm, with a maximum of 26 ppm in the surface sediments. Down deeper, they found PCBs in 117 of 143 samples, with a maximum concentration of 51 ppm at a depth of 6.5 feet.

GE was obligated to at least imagine cleaning Rising Pond. Its options include a thin-layer cap of 3 to 6 inches of clean material; thicker, perhaps geotextile capping; and several scenarios that remove sediments from levels above 3 ppm to levels above 1 ppm.

The less GE does, the more they save. Their No Action option costs nothing. Monitored Natural Recovery, nature covering the PCBs over time, costs only $5 million. And their favorite fallback position, SED 10, FP 9: removing some sediments in the first five miles and in Woods Pond costs $93 million.

Removal is the key word. In its CMS comments, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) questioned the effectiveness of thin-layer capping: “we do not support the use of a TLC for use in floodplains, shallow backwater or riverine settings without prior removal.”

FWS understands the need for removal: “significant areas of habitat will be lost in the near-term so that long-term health of the ecosystem can be reestablished.”

As for Rising Pond, GE’s estimates range from $10.1 million for a thin layer cap to removing PCBs down to one ppm for $106.3 million.

The more removal, the more money. FWS, acknowledging that none of GE’s scenarios completely works, opts for a $394 million cleanup, with $22.5 million to remove 71,000 cubic yards of sediment from 1 to 1.5 feet, and a cap for Rising Pond.

It’s interesting to note that the federal Fish and Wildlife Service cares more about cleaning Rising Pond than the environmental agencies of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Commonwealth doesn’t even mention Rising Pond in its official comments to GE’s CMS. And the only removal/dredging of PCB contaminated sediments they do endorse is the removal of 286,000 cubic yards in Woods Pond. As for the rest of the river, they declare: “perform no bank or river excavation and stabilization because this work is not necessary to meet the human health goals identified by the EPA (due to the low concentrations of PCBs) and will inevitably cause severe and long-lasting destruction of the Housatonic River ecosystem.” Deval Patrick has other places to swim than the Housatonic.

My favorite, SED 8 / FP 7, includes cleaning Rising Pond down to 7 feet, and removing 468,000 cubic yards of sediment. It’s $917 million for a clean Rest of the River.

Here’s to a fishable, swimmable Rising Pond.