By David Scribner

August 30, 2011

Restoring rail passenger service to the New York Metropolitan Area would provide a major boost to the Berkshire economy, both during the reconstruction of the rail line and into the future, as energy efficient access to the Berkshires promotes increased travel, raises property values and encourages the establishment of satellite business operations of New York firms.

Over the next decade, a year-long economic impact study has concluded, the passenger service would pump $625 million into the region abutting the rail line, extending from Danbury, Conn., north to the Berkshires. Of that, $240 million would be realized within the Berkshires, along with the addition of more than 300 jobs.

“The potential benefits of the passenger rail service are substantial,” explained Williams College economist Stephen C. Sheppard, who developed the assessment on behalf of the Canaan, Conn.-based Housatonic Railroad that owns the rail corridor. “The value of the benefits is large compared to the investment. Projects like this have the potential to revive the fortunes of what was once a threadbare manufacturing region by providing the means to establish a diverse, modern economic base.”

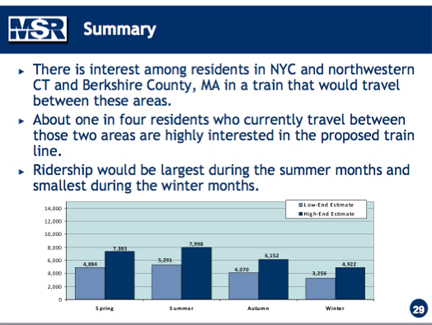

Last year, a marketing study by Market Street Research of Northampton estimated that potential annual ridership would conservatively produce 2 million annual fares from communities along the line from Pittsfield to New York. That level of demand prompted the railroad to commission the economic impact study required for the rail infrastructure upgrade, estimated to cost $200 million for track, signals, stations and rolling stock.

“This is pretty exciting news,” declared Housatonic Railroad President John Hanlon before a press conference at the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission offices in Pittsfield. “Now we have the economic study to justify our application for low interest loans from the Federal Railroad Administration. Over the next year, we will be developing our financial pro forma.”

Hanlon predicted that the initiation of rail service is five years away, with crafting of the fare structure and funding packaging taking at least a year, and the rebuilding of the rail line another three.

“The average commuter rail project takes an average of 14 years to complete,” he reported. “We’re planning on doing this cheaper, better and faster.”

Still, Berkshire officials were enthusiastic about the prospects of rail service.

“These are far better results than I expected,” observed Lauri Klefos, president and CEO of the Berkshire Visitors Bureau.

Hanlon has insisted that the passenger rail service would operate without public subsidy, an uncommon practice in commuter rail networks.

“If this private mode of operation can be made to work, it would be a very exciting model for the rest of the country,” Sheppard noted. “There are few other such systems, one of them being one funded by Microsoft for its employees in Redmund, Wash.”

Colin Pease, the Housatonic’s executive vice president for special projects, pointed out, however, that state and federal officials in both Massachusetts and Connecticut are unaccustomed to dealing with a public/private partnership that involves the private operation of a passenger transportation network.

But Sheppard explained that his research quantified the economic benefits that would be provided the Berkshires. His report found, for example, that rail service would result in 113,000 new visitors per year to the Berkshires, or the equivalent of a creation of a major new cultural venue. Those visitors alone represent an $8 million infusion into the Berkshire economy and the likely creation of 126 jobs.