By Mickey Friedman

July 11, 2011

What do Massachusetts Congressman John Olver, Sen. Scott Brown, General Electric, and officials at the Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs all have in common?

Together, they’re doing their best to influence the Environmental Protection Agency.

They’re trying to intervene in EPA’s internal process and delay a cleanup decision for the “Rest of the River.” The “Rest of the River” is the name given by the EPA to the PCB-contaminated Housatonic south of the confluence of the East and West branches. The heavily-contaminated first two-mile section of the River in Pittsfield has already been cleaned.

Finally, after decades of peer-reviewed scientific studies of the fish and frogs and ducks and benthic invertebrates, the detailed computer-modeling plan of how the river flows, how and where the PCBs move, the EPA is crafting a clean-up plan.

The way the process works is EPA takes GE’s suggestions as presented in its more than 1,000-page Corrective Measures Study (CMS), checks all the public comments from interested parties and analyzes all the data it has collected over the years and comes up with a plan.

The EPA is bound to consider certain criteria when proposing a remedy. These include protecting human health and the environment; complying with a host of federal requirements under other statutes like the Clean Water Act; the long-term reliability and effectiveness of the remedy; the reduction of toxicity, the ability of the contaminants to move, and the volume of contamination; the ability to implement the solution; and finally, the cost of the remedy.

The EPA is just about ready to present their Proposed Plan to the EPA’s internal Remedy Review Board, made up of EPA experts from all over the country. These are engineers and scientists and project managers who have cleaned up other contaminated sites. Their task is to go over the Housatonic River plan from top to bottom to point out problems. The idea is to draw on the collective wisdom of the best experts to craft the best plan.

Then the plan goes through another public comment process.

According to a June 21 letter from Congressman John Olver to EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson, Region One of the EPA, the folks responsible for studying and cleaning the Housatonic River, need to take a time out. Why? Because GE and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts have been complaining that the EPA is rushing things, and that the EPA hasn’t listened to the Commonwealth’s concerns or allowed them to participate in the process, and hasn’t really properly appreciated the Commonwealth’s own plan for a cleanup. In Olver’s words:

As stewards of the river and the surrounding ecosystem, state environmental officials want to be assured that the procedures to be implemented will meet their constituencies’ health and environmental standards, provide a comprehensive cleanup of PCB’s and refrain from being overly invasive to habitats and the scenic resources of the river.

In his June 29 letter to Jackson, Sen. Scott Brown goes a bit further:

I am troubled … that a submission to the Remedy Review Board at the time will prevent state and local environmental officials’ as well as other affected parties’ concerns from being addressed. Many are concerned that the Board will simply rubber stamp EPA’s preferred alternative and the subsequent comment period will yield little to no changes …

State environmental officials need assurance that the plan to be implemented will meet health and environmental standards, clean up PCBs, and refrain from being overly invasive to the scenic portions of the river.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, writing to Jackson on June 23, is openly quite critical of the EPA:

Specifically, we believe that submission of a proposed remedy to the Remedy Review Board (RRB) drives a rush to judgment with insufficient sharing of information and discussion with the Commonwealth, deprives the Commonwealth of adequate opportunity to shape the remedy, and will likely result in a proposed remedy that will cause significant ecological harm.

The Commonwealth goes on to ask for more time to join GE and the EPA “in an effort to find common ground prior to the submission of a remedy.”

As a long-time participant in what has seemed like a tortuously slow process – study after study, delay after delay, beginning in the early 1980s — I find it a bit difficult to take at face value the Commonwealth’s claim of a “rush to judgment.” Nor Rep. Olver’s and Sen. Brown’s concern that the Commonwealth hasn’t had an opportunity to participate. I’ve attended dozens of meetings hosted by, or attended by, representatives of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

What seems to really be at work here is a profound difference of opinion. The EPA is bound by the legal requirement to base its cleanup decisions on science – the levels of PCB contamination, the distribution of PCBs, the human health effects that might occur because of this contamination, the environmental health effects that might occur, etc. One might presume that the Commonwealth would also be bound by science. But it turns out you can manipulate the science, especially if you decide that the environmental health effects aren’t that important after all.

This is what GE wrote on page one of its Executive Summary to the CMS:

When it comes to the Rest of River, less really is more. The least intrusive approaches to cleaning up river sediment and floodplain soil will meet EPA’s human health criteria, are protective of the environment, and are far more likely to achieve that goal without destroying a river to clean it.

This is what our top Massachusetts environmental officials wrote in their February 7, 2011 letter to The Berkshire Eagle:

Removing all the PCBs from the river bottom, banks and adjacent floodplain would require massive tree-cutting, dredging, soil removal, construction of new roads and staging areas, and elimination of habitat for plant and animal species found nowhere else in the commonwealth. We must make GE remedy the damage it has caused, but we must not destroy the river in order to save it.

GE and the Commonwealth share a common narrative. It begins with the cleanup of the most heavily contaminated sections of the Housatonic River. The first half-mile of the river flows through GE’s industrial plant.

A little history: From the mid-1930s on through 1977, PCB-contaminated oil went down the drains of GE’s factories and underground, forming vast plumes of oil. This oil seeped into the Housatonic River. GE’s gigantic oil storage tanks on Peck’s Bridge leaked. The storage system by Building 68 alongside the river leaked from 1,000 to 3,000 gallons of PCBs into the river. And GE workers routinely dumped waste along the river banks, sometimes into the river itself. More than a million and half pounds of PCBs made it into the river.

In 1997 and 1998, GE was forced to excavate a small section of the river, removing 5,000 cubic yards of contaminated river sediments. The average PCB levels were 1,534 parts per million (ppm). They removed more than 2,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil from the banks. The average PCB levels on the surface were 720 ppm; below the surface, 5,896 ppm. As a point of reference, the Massachusetts DEP regards levels of just two (2) ppm and above in backyard soil to present a health danger to people using that backyard.

Here are two pictures showing what the EPA and GE found when they began to dredge the first half mile:

GE and its friends have got a great slogan: “Don’t destroy the river to save it.”

They’ve got a great — but profoundly inaccurate — story that goes along with the slogan. It goes like this: several years ago the EPA came in and made GE clean the first two miles of the river in Pittsfield. Using cranes and backhoes, GE dredged and scooped and scraped the PCBs out. And while they may have gotten rid of the PCBs, they really messed up our beautiful River, its beautiful riverbank, for forever and ever and ever. They traumatized the fish and frogs and the plants and the vernal pools. As a result, that section of our beautiful River is gone.

Lots of people are telling the story. Here is Mayor James Ruberto of the City of Pittsfield:

Over the last ten years, an aggressive approach has been taken to rid the prime source of PCB contamination in the first two miles of the Housatonic River. While this approach dramatically reduced the level of contamination, unfortunately the bank to bank dredging resulted in substantially altering the ecosystem of the Housatonic River. (Mayor Ruberto, Comments to EPA on GE CMS, January 24, 2011.)

Michael Daly, president of Berkshire Bank and a leader of the GE-funded 1Berkshires told the Berkshire Eagle:

We couldn’t have the rest of the river done in the same manner as the first mile was done and that it would cause tremendous harm in many ways.

I think that people will find out that if there is a dredging of this river from end-to-end that it is logistically impossible to do, and that it will have decades of devastation that would be hard for the Berkshire community to overcome.

The Berkshire Chamber of Commerce wrote to all its members urging them to pressure EPA:

Extensive dredging would devastate the River and negatively impact tourism, the Berkshire County economy and our quality of life for years, if not forever. We cannot allow this to happen.

In case you don’t know what a destroyed river looks like, GE’s film “Fate of the Housatonic River,” uses movie magic to create one for you:

Or GE’s movie version of what the EPA will do to the floodplain?

The film’s narrator tells the story of what the EPA will accomplish:

Once the work is finished, kingfishers, muskrats, and bank swallows will be unable to burrow into the remediated riverbanks. Miles of prime habitat will be destroyed. The animals that use these banks for shelter and breeding grounds will disappear. The shady, wild Housatonic of today will disappear into history. In the best case, it would take at least half a century for these forests to be what they are today. The animals that rely on these forests won’t be able to wait. Generations will grow up alongside the river that bears little resemblance to what it once was.

Thanks to GE, the Berkshire County League of Sportsmen sent its members a free DVD copy of the GE movie, then asked them to tell the EPA: “Don’t destroy the River to fix it.”

In the real world, remediation work for the first half mile began in October 1999 and was completed by September 2002. In 2007, GE went back into the first half mile of the River to take sediment samples to test for the presence of PCBs. Of the 51 samples taken, 45 samples (88 percent) had PCB levels of less than one ppm and of the six remaining samples above one ppm, four were taken from sub-surface samples. Considering the very high levels the EPA and GE began with, the remediation appears to have been remarkably successful.

From 1,534 parts per million to 1 parts per million. From remediation to restoration: from 1999 to 2003 to 2009 – Photos EPA

As an integral part of the process, the EPA brought in a team of river restoration specialists to come up with a plan to restore the first two miles once the remediation was done. They planted native species of trees and plants, recreated the ecology of the vernal pool, and created ways to restore and enhance the organic movement of the River. River restoration activities were substantially completed by the end of 2006. The EPA then conducted a series of studies to ensure the work was successful.

Here’s what the mile and half remediation looked like:

Then the DEP took this picture in July 2008 of a section of the mile and a half remediation:

Three years later on June 8, 2011, the DEP returned to check on the state of the mile and a half cleanup. This picture was taken:

Yes, you can see the remnants of the bank stabilization measures they employed, but clearly the River has healed more quickly than you might have imagined.

But aside from aesthetics, what of the PCB levels and the health of the wildlife in the mile and a half? The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers performed extensive sampling. Here is a summary of the results:

The sediments collected in remediated and restored areas of the 1.5 Mile Reach have total PCB concentrations ranging from non-detect … to 1.9 ppm with an average total PCB concentration of 0.17 ppm. (Post-Remediation Sediment Sampling Report 1.5-Mile Reach Removal Action, 4.)

It seems to me that this is a very impressive reduction: from an average concentration of PCBs of 29 ppm down to less than one ppm.

But what about the fish and other wildlife? In 2007, the Army Corps performed its Post-Remediation Aquatic Community Assessment of the mile and a half. They checked the health of benthic macroinvertebrates, the aquatic organisms, typically insects of the river bottom. They had checked benthic macroinvertebrates in 2000 before they began the cleanup, and so they had a clear before and after comparison. This is what they found:

A substantial decrease in tissue PCB concentrations, a reduction of more than 99 percent between the 2000 and 2007 collections, is evident and indicates the effects of the remediation, which was also reflected in the sediment PCB concentrations. (6)

Of fish, the Army Corps wrote:

The abundance and diversity of fish species identified appears to indicate good water and habitat quality.

Significantly lower PCB levels in the Housatonic River and in the living things that make the river their home. A restoration plan that is working.

So much for the story of a river destroyed by a cleanup. Instead we have a river cleaned by a cleanup. Instead of a story of failure, we have a story of success.

But the Commonwealth wants the EPA to hold up and slow down. What are they offering?

“The Commonwealth is concerned that in some areas the remediation of PCBs may result in destructive ecological impacts to this rich and unique system. We therefore propose an alternative: a phased, long-term remedy that minimizes human health risks posed by PCBs in the environment, while at the same time taking care to weigh potential benefits of remediation against potential injury to the ecosystem. Our proposed approach is to remove PCBs when needed to protect human health, or when compelling goals may be achieved without causing ecological harm. This means that our approach leans away from performing intrusive work in the name of meeting purported ecological goals; because in virtually all instances the actual and inevitable damage to this existing, unique ecological resource will far exceed the theoretical benefit of lower PCB concentrations.” (Page 1, Commonwealth of Massachusetts CMS Comments, January 31, 2011)

There are several phrases here that are deeply troubling. First, there is the insinuation that federal EPA regulators would substitute their own arbitrary standards for the science they are bound to respect. Exactly what “purported” ecological goals are the EPA staff trying to foist on us? And for what purpose?

The second insinuation is equally troubling. That the EPA would actually damage the River to win some theoretical victory of lower PCB levels. If you truly appreciate that there is no safe level of PCB contamination, you will appreciate the importance of removing as many PCBs as possible, and by lowering PCB concentrations and by limiting — hopefully removing — the pathways of exposure. As with many toxins, the more intensive and skilled our investigations are, the more we understand that even exceedingly low levels of many toxic chemicals have adverse health effects. PCBs, especially because they mimic human hormones, have complex effects on human development that we are just fully appreciating. And we are also learning to our surprise that the volatilization of PCBs, and our breathing in of airborne PCBs, are a major source of exposure.

And when you’re dealing with an extraordinarily toxic chemical like PCBs, how can you even question the benefit of lowering their concentrations?

The Commonwealth plan includes a cleanup of Woods Pond but that’s pretty much it. They don’t want the riverbanks cleaned or the floodplain cleaned because that will endanger the wildlife and destroy the unique character of the river.

The Commonwealth makes the unsubstantiated claims that the EPA can’t perform or supervise removal of PCBs in the contaminated floodplain or on the river banks that wouldn’t inevitably cause severe and long-lasting destruction of the Housatonic River ecosystem and state-listed rare species. Such destruction far outweighs any environmental benefits from PCB removal …

Would it be difficult? Certainly. But impossible? I don’t think so. In any event, where is the scientific analysis to back up such a claim?

Instead of removing the PCBs, a clear and present danger to humans and wildlife, the Commonwealth suggests a bunch of institutional controls. A fancy way of saying if the Commonwealth gets its way: We’ll have a bunch more signs saying you shouldn’t eat the fish and frogs and turtles and ducks. We’ll have boot-washing stations on the poisoned land that borders the River. So if you get the PCB-contaminated dirt on your skin, or breathe in the dust, at least you can clean your shoes.

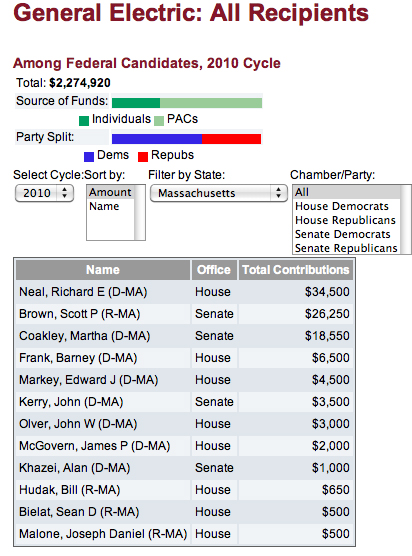

So why are Scott Brown and John Olver intervening on behalf of the Commonwealth and GE? I can only speculate. But here’s something to think about. In the 2010 election cycle, Scott Brown got $26,250 from contributions from GE’s PAC and its employees. John Olver got $3,000 from GE.

Here’s a chart from opensecrets.org showing the local recipients of GE’s generosity:

The company spends a fortune lobbying members of Congress to influence the EPA. In 2010, GE spent $39 million on lobbying. Remember Peter Larkin, state representative from Pittsfield? He’s a GE lobbyist — and he and his associates have been paid $433,221 over the last five years by GE to lobby on Beacon Hill. Remember Bob Durand, friend of the environment, fisherman, hunter, former Massachusetts Secretary of the Department of Environmental Protection? Well, he’s a GE lobbyist, too.

According to a 2010 article on the NBC Los Angeles website – and GE owns NBC so they might know what they’re talking about – GE has been forced to spend a lot of money they didn’t want to spend on the Pittsfield/Housatonic cleanup so far:

Since 1990, GE says it has spent more than $495 million on this project, including more than $426 million on its environmental investigation and cleanup at its former transformer plant and nearby areas.

That’s $495 million to clean up contaminated properties throughout the city and for the first two miles of the Housatonic. And so it’s not out of the question to imagine that cleaning the next ten miles might cost them more than a billion dollars.

Clearly, the stakes are high for everyone.

The EPA has proven with the cleanup of the first two miles of the Housatonic that they know how to clean rivers without destroying them.

It seems pretty clear that GE and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts don’t want to really clean the river. If, with the help of John Olver and Scott Brown, they get their way, we’ll have a poisoned river forever.